The author John Mark O’Leary MRCVS is an assistant professor at the UCD Veterinary Teaching Hospital in Dublin, Ireland. He is an expert in the endodontic dental treatment of horses and invites readers to participate in his PhD research – see more details below…

Dental infections in horses involving the inner living part of the horse’s tooth – the pulp – can cause pain or discomfort that leads to reluctance to drink or eat in some cases, or to avoid riding. But the signs can also be extremely subtle with only minor changes in eating, biting and general behavior.

Why do horses get dental infections?

Unlike humans, whose very common cases of tooth decay and related infections are linked to diet, tooth fractures are a more common cause of pulp damage and inflammation in horses’ teeth.

In a horse’s front teeth (the incisors) problems are usually associated with a broken tooth, often associated with a history of falling on the road.

A horse with broken front teeth. Credit: TI Media

Cradle-biting horses can wear down their front teeth faster than they grow naturally – resulting in the sensitive pulp being exposed. Once the pulp is exposed, it will become contaminated with food and bacteria from the mouth, which leads to infection.

Besides broken teeth, the other most common cause of inflammation in the pulp of the horse’s cheek teeth (molars) is a local bacterial infection that spreads through the natural openings at the edge of the tooth root deep into the gum (the apical foramen) without any change to the outer surface or crown of the tooth. This is more common in horses under six years of age.

Other causes include over-drilling or over-drilling with powered dental drills and equipment.

How can I tell if my horse has a front tooth infection?

If a horse’s front teeth are affected, they may show reluctance to drink cold water or take hay from hay, or avoid riding behavior. Horses suffering from an acute case usually resent the exposed pulp being probed with dental equipment, which leads to active bleeding.

However, once the infection becomes established, often with food filling the cavity leading to death of the pulp and loss of nerve supply (pulp necrosis and denervation), then there may be no obvious behavioral symptoms or avoidance reactions on detection.

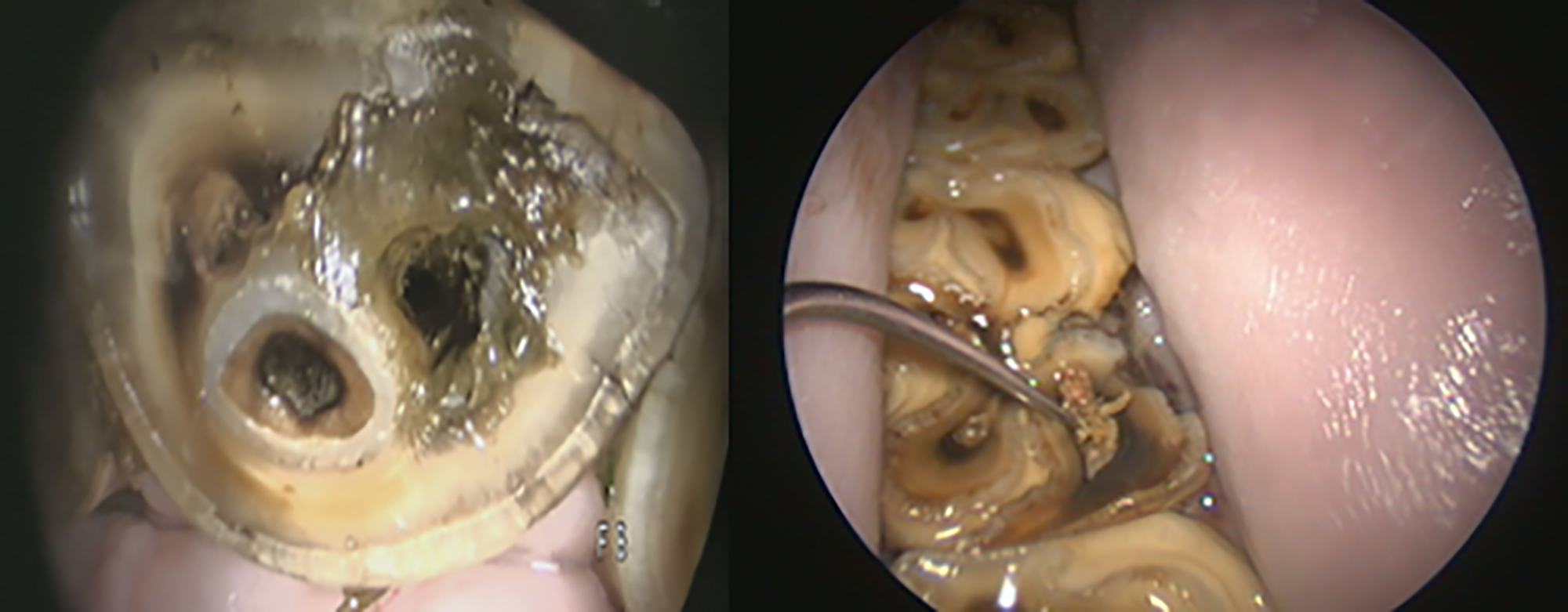

Dentin defects on the surface of a mandibular incisor and mandibular tooth with associated food contamination and chronic endodontic infections. Credit: John Mark O’Leary MRCVS

The infection can eventually spread through the natural openings at the edge of the tooth’s root (apical foramen) to invade the tissues around the tooth (periodontium). At this stage, receding gums or drainage of infected passages may develop.

How can I tell if my horse has a cheek tooth infection?

Acute infections involving the horse’s cheek teeth usually show little or no obvious signs unless a displaced tooth fragment causes damage to the soft tissue inside the mouth. Recent behavioral studies have reported subtle changes in eating, biting, and general behavior associated with cheek tooth infections.

When an established pulp infection reaches the top of the last four upper cheek teeth, the bacteria can move into the sinus chambers above, leading to discharge of pus from the nostril on that side of the face.

Chronic infections that reach the roots of other teeth in the cheeks may appear as bony swellings in the face, with or without pus from the drainage tracts.

Cases with obvious surface defects in the tooth are often found during routine dental examinations. Determining the extent and severity of an infection may require referral to a specialist equine veterinarian.

The specialist will usually perform a detailed oral examination with a camera and evaluate the reserve crown and roots using diagnostic imaging. Where x-rays are unable to clearly identify the problem, a more sensitive imaging modality, usually a computed tomography (CT) scan in a hospital setting, may be necessary.

How are dental infections in horses treated?

Endodontics is the name of the specialized branch of dentistry that deals with infections involving the pulp of the tooth.

There are three treatment options:

● Vital pulp therapy (VPT), in which all or part of the dental pulp is preserved

● Root canal treatment (RCT) where the pulp is completely removed up to the end of the root

● Extraction, where the entire tooth is removed.

Endodontic treatment for horses

The extent and severity of infection within the pulp and around the root tip (apical) will determine whether either VPT or RCT is feasible. Treatment is usually performed on a standing, sedated horse under local anesthesia.

The four typical steps of endodontic treatment are:

● access with motorized dental drills, usually through the overlying dentin defect on the occlusal surface.

● removal of dead, damaged or infected tissue (debridement) with dental root canal files and disinfection of the endodontic system.

● local application of a dentin stimulation product to the remaining viable pulp tissue and

● Finally applying an airtight seal (in the form of a seal) inside the cavity created with material that will wear at the same rate as the tooth

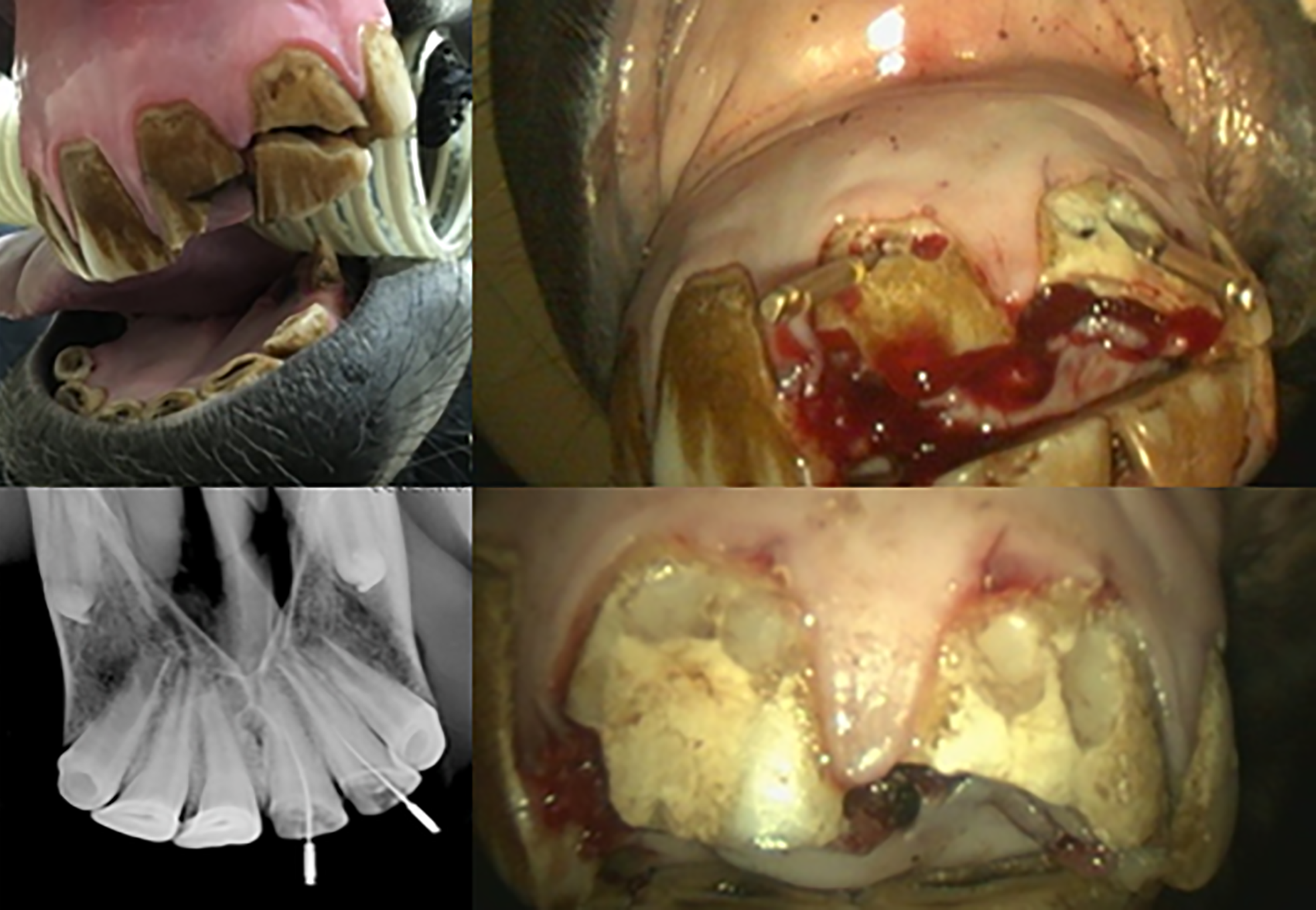

Upper left: acute fracture of upper central and lateral incisor with pulp exposure. Top right: direct endodontic access to the pulp horns at the gingival margin. Bottom left: X-ray guidance of cleaning depth with dental records. Bottom right: the remaining vital pulp was medicated and the access cavity was sealed with composite resin cement. Credit: John Mark O’Leary MRCVS

Where appropriate, VPT is usually the preferred treatment procedure in acute cases. This is because it optimizes the pulp’s ability to return to normal function. It creates a hard dental bridge that protects the remaining pulp and maintains blood supply, innervation and immune functions. VPT also avoids having to negotiate the complex root canal system.

RCT is used for more severe and chronic tooth infections. It involves removing the entire pulp and disinfecting down to the level of the natural openings at the edge of the tooth root into the gum (the apical foramen). This is followed by the application of tooth-stimulating medication at the root level. The rest of the cavity is sealed at the top of the tooth (the occlusal plane).

Often a diseased cheek tooth is still partially healthy and only part of the pulp needs to be accessed and treated. In such a case the inside of the tooth is now inactive, but the tissues surrounding and supporting the teeth (periodontium) remain healthy and the tooth should erupt normally and remain functional for chewing. However, the lack of full vitality predisposes the tooth to subsequent development of cavities and fractures.

Extraction of horse teeth

Extraction is typically chosen for established infections that extend into the tissues surrounding and supporting the teeth or previous failed endodontic treatments, but it is not without risk.

Common long-term conditions after cheek tooth extraction are overgrowth of opposing teeth and displacement of adjacent teeth into the cheeks, with increased risks of food entrapment and subsequent inflammation of the tissue surrounding the tooth (periodontitis).

A horse may need a period of forced rest if an extraction complication occurs, so if competing, surgery is best scheduled out of competition.

Importantly, equine athletes showing no obvious signs of infection (subclinical) can be treated with endodontic techniques to allow the horse to continue to compete for a season, with extraction scheduled for the off-season.

How successful is the treatment of equine dental infections?

Equine endodontic treatment has improved over the past 10 years through anatomical studies, improved adaptation of human techniques, and availability of better materials.

Infected teeth may require two treatments a month apart to adequately clean the pulp cavity, with long-term success rates of 75% for incisors and 80% for cheek teeth.

Most specialists are reluctant to present such a favorable outlook for RCT of cheek teeth given the lack of procedural sterility and microscopic guidance for adequate cleaning of the pulp chamber and root canals as required for patients. Re-examinations are often required at three and six months postoperatively and then every two years.

Endodontic treatment is rarely a one-step process as it can be complex, expensive and time-consuming. A significant investment in training and equipment will be required by the treating physician to select and complete the appropriate endodontic technique to optimize success. It is important that horse owners are fully informed before treatment begins to help manage their expectations.

How you can get involved

The author of this article invites H&H readers to take part in a short survey to aid his PhD research in this specialist area of equine dentistry. If you want to join, please visit horseandhound.co.uk/endodontic-survey

You may also be interested in…

Credit: Alamy Stock Photography

The view inside a horse’s mouth showing wolf teeth in front of the premolars.

Credit: Alamy Stock Photography

Bon moins expressif, essaye un peu de sourire

Credit: Future