A new study shows that a topical gel that blocks the receptor for a metabolic byproduct called succinate can effectively treat gum disease. By suppressing inflammation and changing the composition of bacteria in the mouth, this gel could offer a non-invasive solution to a widespread problem. Researchers from the NYU College of Dentistry led this work, and their findings were recently published in Cell references.

Gingivitis, or periodontitis, affects nearly half of adults age 30 and older. It is an inflammatory condition involving three main components: inflammation of the gums, an imbalance between harmful and beneficial bacteria in the mouth, and damage to the bones and structures that support the teeth. If left untreated, gum disease can lead to painful symptoms such as bleeding gums, difficulty chewing, and eventual tooth loss.

Current treatments for gum disease are limited. As Yuqi Guo, research associate at the NYU College of Dentistry and one of the study’s co-authors, explains, “No current treatment for gum disease simultaneously reduces inflammation, limits disruption to the oral microbiome, and prevents bone loss. There is an urgent public health need for more targeted and effective treatments for this common disease.”

The study builds on earlier research that linked elevated levels of succinate, a molecule produced during metabolism, to gum disease. Higher levels of succinate are associated with increased inflammation, a characteristic of periodontitis. In 2017, Guo and her team discovered that excess succinate activates a receptor that contributes to bone loss, making this receptor a promising target for therapy.

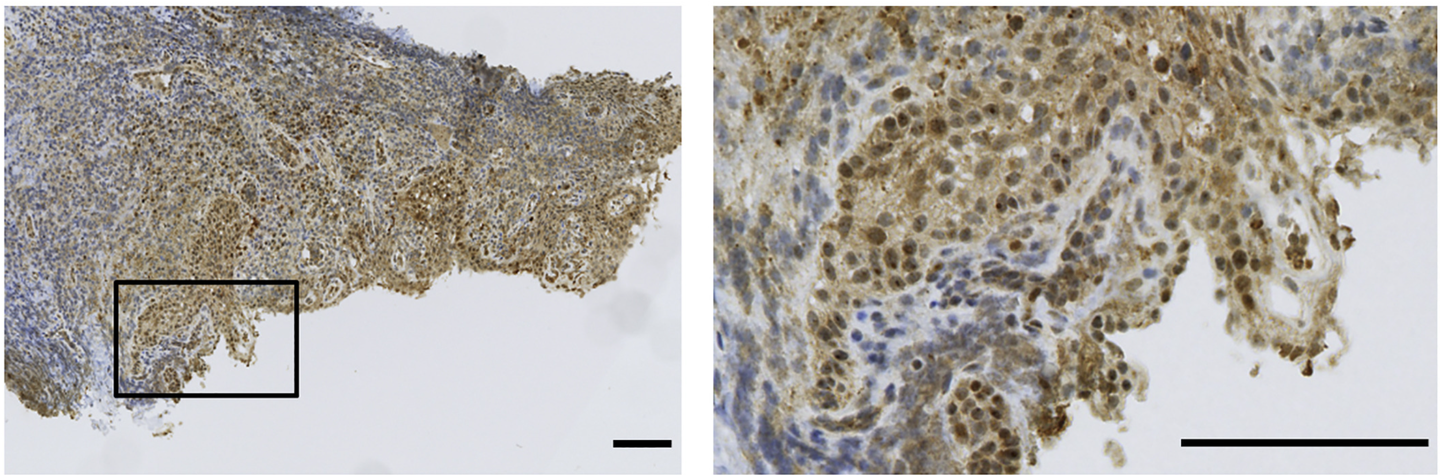

The researchers confirmed the link between electricity and gum disease by analyzing dental plaque from humans and blood from mice. They found higher levels of succinate in both humans and mice with gingivitis compared to those with healthy gums. They also identified the presence of the succinate receptor in the gums of both species.

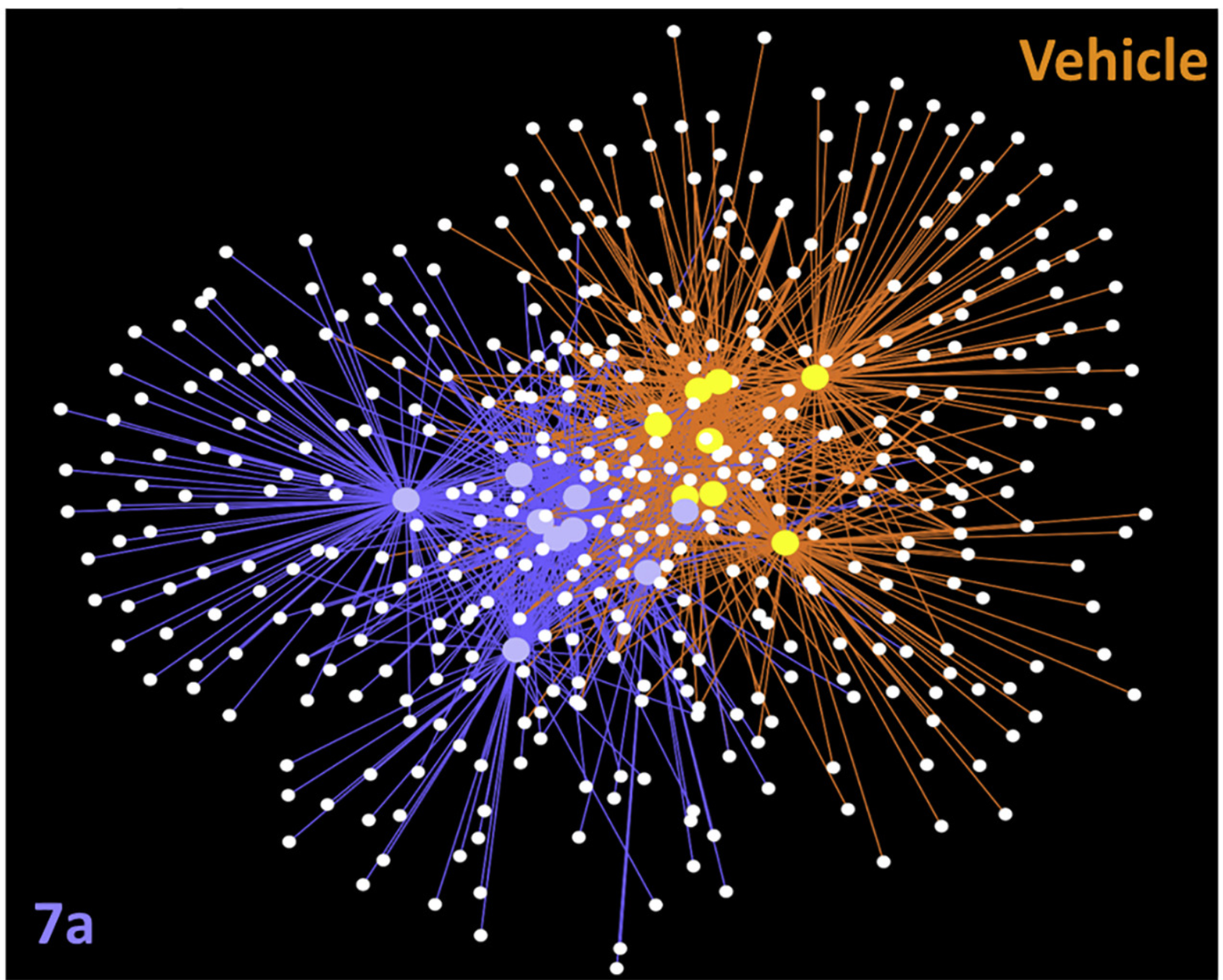

To investigate this further, the team genetically modified mice to knock out the succinate receptor. These knockout mice showed lower levels of gum inflammation and bone loss compared to normal mice. They also had a healthier balance of bacteria in their mouths. Even when the researchers introduced extra succinate, which worsened gum disease in normal mice, the knockout mice remained protected.

“Mice without active electren receptors were more resistant to disease,” says Fangxi Xu, a research assistant at NYU Dentistry and another co-author of the study. “Although we already knew there was some connection between succinate and gum disease, we now have stronger evidence that elevated succinate and the succinate receptor are the main drivers of the disease.”

Based on this discovery, the team developed a gel designed to block the electrical receptor. In laboratory tests with human gum cells, the gel reduced inflammation and bone loss. The next step was to test it on mice with gum disease. Applying the gel to their gums significantly reduced inflammation and bone loss within just a few days. One trial showed that applying the gel every other day for four weeks cut bone loss in half compared to untreated mice.

In addition to these benefits, the gel also changed the bacterial makeup in the mouths of the treated mice. Pathogens from the Bacteroidetes family, which are commonly associated with gum disease, were significantly reduced. Importantly, further testing showed that the compound did not act as an antibiotic, meaning it did not directly kill the bacteria, but instead worked by modulating inflammation.

Deepak Saxena, professor of molecular pathobiology at NYU Dentistry and co-senior author of the study, explains, “This suggests that the gel changes the bacterial community through the regulation of inflammation.”

While the results are promising, more research is needed to determine the best dose and timing for the gel, as well as to ensure there are no harmful side effects. The goal is to create a version that people can use at home to prevent or treat gum disease, as well as a stronger formulation for professional use in dental offices.

The long-term vision includes the development of an oral strip or slow-release gel that can be applied to areas affected by gingivitis. According to Xin Li, professor of molecular pathobiology at NYU Dentistry and lead author of the study, “Current treatments for severe gum disease can be invasive and painful. In the case of antibiotics, which may help temporarily, they kill both good and bad bacteria by disrupting the oral microbiome. This novel compound that blocks the succinate receptor has clear therapeutic value in treating gum disease using more targeted and convenient procedures.”

The treatment of gum disease is currently far from ideal. Surgical options can be invasive, painful and expensive, while antibiotics can temporarily help but run the risk of wiping out both harmful and beneficial bacteria, upsetting the natural balance in the mouth. This new gel offers a potential solution that targets gum disease at its root, blocking the pathway responsible for inflammation and bone loss.

If successful, this topical gel could represent a game changer in the battle against gum disease, providing a more comfortable, non-invasive option for millions of people. It could also reduce the need for antibiotics, which often do more harm than good by disrupting the delicate balance of bacteria in the mouth.

With further development, this gel could soon become a staple household product for the prevention and treatment of gingivitis, giving you a more effective way to maintain oral health without the inconvenience of traditional treatments. For those already suffering from gum disease, this gel may just be the breakthrough needed to stop the disease in its tracks, restoring both dental comfort and health.

Additional study authors include Scott Thomas, Yanli Zhang, Bidisha Paul, Sungpil Chae, Patty Li, Caleb Almeter and Angela Kamer of NYU Dentistry. Satish Sakilam and Paramjit Arora of the NYU Department of Chemistry. and Dana Graves of the University of Pennsylvania School of Dentistry.