September 03, 2024

2 minutes reading

Basic foods:

- Thirty patients underwent tooth extractions with an average of 8.5 extractions immediately after radiation therapy.

- Thirteen of them developed exposed alveolar bone.

Dental extractions after radiation therapy to the head and neck should not be performed routinely because of significant risk, according to the results of a prospective cohort study.

“If you can’t remove the teeth before radiation, then treatment without extraction is probably the best approach.” Matthew C. Ward, MD, A radiation oncologist in the division of radiation oncology at the Levine Cancer Institute at Atrium Health, told Healio. “It may be safe to do extractions after radiation if the dose to the mandible/oral cavity is low enough.”

Guidelines recommend extracting teeth that cannot be restored before patients receive radiation therapy to the head and neck. However, extractions before radiation can cause delays in treatment.

Ward and colleagues evaluated the feasibility and safety of performing dental extractions immediately after radiation therapy.

The prospective cohort study included 50 patients who were unwilling or unable to have at least one dental extraction prior to head and neck radiation therapy.

Study participants received dental care at an academic department and received cancer care at regional centers. The researchers recommended that dental extractions be performed within 4 months of completing radiation therapy.

Alveolar bone marked by any practitioner after extraction served as the primary endpoint.

Thirty-two (64%) patients had nonoperative radiotherapy and 18 (36%) had postoperative radiotherapy. All patients received intensity-modulated radiation therapy.

Twenty patients refused tooth extraction immediately after radiotherapy. The other 30 underwent a median of 8.5 extractions (range, 1–28) at a median of 64.5 days (range, 13–152) after completion of radiation therapy.

Median follow-up for survivors without exposed bone was 26 months (interquartile range, 17–35) after radiation therapy.

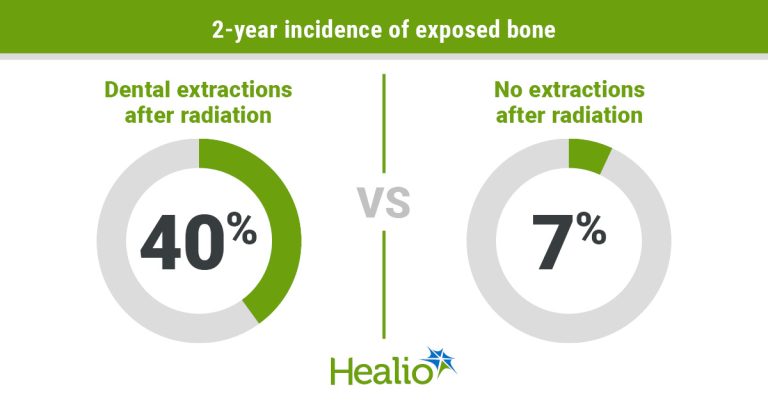

Results showed a 27% (95% CI, 14–40) cumulative incidence of any exposed bone at 2 years, with a higher 2-year cumulative incidence of exposed bone among those who underwent dental extractions after radiation than among those who did not (40 % vs. 7%).

Among the 13 patients who developed exposed bone, eight had confirmed osteoradionecrosis. Four cases were solved and one person was lost to follow-up.

The researchers acknowledged study limitations, including the small cohort in the single-institution pilot study, the lack of long-term follow-up, and the fact that patients in the cohort had varying sites of primary cancer, which may have different rates of osteoradionecrosis.

“If teeth could be safely removed after radiation, it would speed up the time to cure cancer,” Ward told Healio. “Unfortunately, that doesn’t seem to be the case. However, the possibility [osteoradionecrosis] seems low in the early years, so if it’s medically necessary to start cancer treatments quickly, providers should feel comfortable starting without export.”

Ward added that he would like to see a randomized trial comparing extractions before radiation therapy versus observation.

“It’s not clear whether the export is useful at all,” he said.

For more information:

Matthew C. Ward, MD, can be reached at matthew.ward@atriumhealth.org.